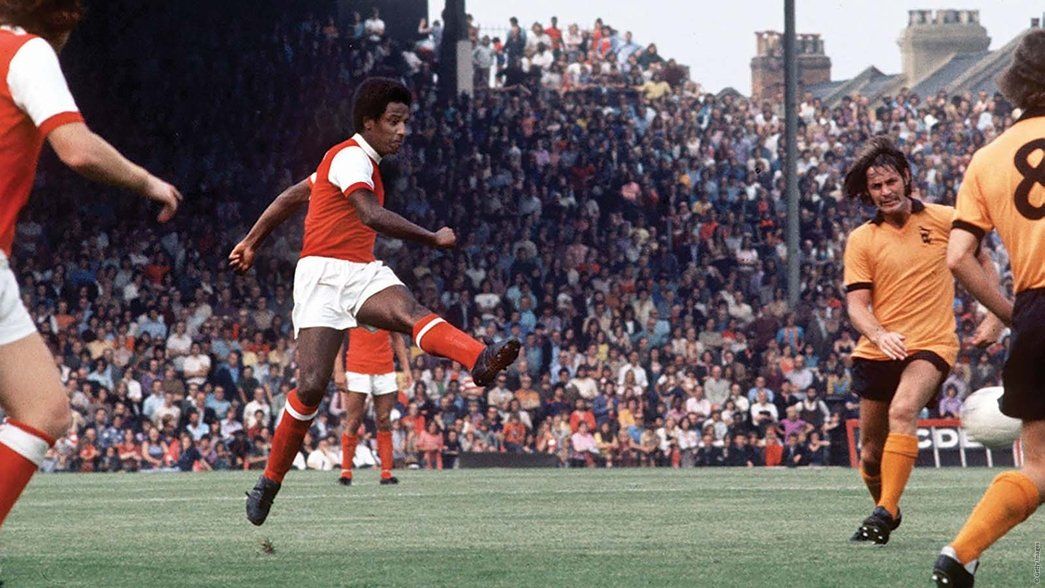

Every issue, we hear exclusively from significant figures at the club on our Official Voice pages of the programme. This issue, we hear from the first black player to represent the club, Brendon Batson, who made his debut nearly 50 years ago.

When I look back on my experiences with Arsenal, the club was fantastic to me.

It was a great place to grow up at in my formative years, where I was taking my first steps into the professional ranks. Bertie Mee was the manager when I was coming through at Arsenal and he was an exceptional individual. You had people like Don Howe, Steve Burtenshaw and later on, Dave Smith.

I remember my debut being a bit of a shock. It was away at Newcastle and, at the time, the way Bertie Mee and his coaching staff would introduce young players into the first team would see us travel with the squad to experience the feeling of what was that like.

I remember coming on for Charlie George just after half-time as he was feeling unwell. It was a miserable day in the north east and the game went by like a flash. There was a clash between Malcolm Macdonald and Alan Ball, which was really interesting. The difference in volume when they had a shouting match was quite memorable!

My appearance in that match saw me become the first black player to represent Arsenal’s first team – although that wasn’t something I actually knew until many years after I retired. It wasn’t of any great significance to me at the time – and I still feel a little bit indifferent towards it now, if I’m honest. I was just trying to make my way and colour didn’t come into it.

I came to England when I was nine years old. It was then that I started to experience racism. It was just something the black community grew up with. Once I was in the professional ranks, the volume of racist abuse increased depending on how many people you were playing in front of. It wasn’t anything new to me though because I’d experienced it as a schoolboy growing up.

I got it from the opposition when I played as a schoolboy. One of the good things in the professional ranks was that it was almost unheard of that you’d get racist abuse from opponents. It happened occasionally, but it was very seldom. That was one of the positives about playing professionally.

At schoolboy level, it was something you experienced on a game-by-game basis, and in everyday life too. I’d often have people – even children – shouting racist abuse at me from car windows. I remember an incident on the London Underground where my partner and I were being abused. What was good was that a lot of people came to our aid – there’s always been more good than bad in society in that respect.

I grew up at a time where there were few black players in the game. When I went to West Bromwich Albion, I joined Laurie Cunningham and Cyrille Regis and we played together for 15 months before Laurie went to Real Madrid. At the time, we knew we’d get a lot of headlines because West Brom were the first team to consistently play three black players in the first team.

When I stopped playing and reflected on my career, you realised that the black community were really proud of what we did at West Brom. We just wanted to be known as players. I can’t remember anyone referring to Pele as a black player – he was just Brazilian and Eusebio was just Portuguese. What used to drive me mad on these shores would be the headlines like ‘Black Flash’ or ‘Black Pearl’ when somebody had played well. It was always about the colour rather than the player.

In my opinion, the real seminal moment was Viv Anderson winning his first senior England cap in 1978. It’s important to remember that Viv was selected because he was the best player in his position and not because he was black. After that, more black players came to the fore.

There was that Arsenal team with Paul Davis, Rocky Rocastle and Mickey Thomas as the fulcrum of it – and that was absolutely fantastic. When I was growing up, there was a whispering campaign about black players. People would say not to go near us – they said we were lazy, we couldn’t tackle, we wouldn’t work hard. It was nonsense based on pure ignorance. To see the engine room of a team like Arsenal dominated by three black players was a wonderful sight. To this day, Arsenal still have one of the most ethnically-diverse fan groups around – and I believe a big part of that is down to those three players. In the end it became the norm rather than the exception.

Success on the pitch has been a key vehicle of progress. The visibility of seeing black players thriving has had a huge impact. If you can’t see it, you can’t aspire to become it. Black children playing football in the park were given role models and I think that opened their eyes up to realising that they could make it in the game.

I feel Kick It Out had a big impact as well. Lord Ouseley and the PFA got together and took on his idea. We need to remember it’s not just about Black players – it’s about players from every background. You’ve got people in the modern age like Jordan Henderson, who has really stepped up in support of Black Lives Matter. Players are much more confident in addressing social issues. In the past, we didn’t have that platform or the encouragement.

I was told recently that 40 per cent of all Arsenal debutants in the Premier League era are of black origin. It is an interesting stat and when you see something like that, you realise how far we’ve come from the days of Black players being very much a minority. It’s certainly progressive but we’ve still got a lot of work to do.

The outpouring of love we saw after the Euro 2020 final was fantastic. Good always trumps bad, particularly in this debate. Bukayo Saka seems to have come out of it without losing his confidence on the pitch – and I’m sure that’s in part because of the love and support he’s received from the club and Arsenal supporters, as well as his family members.

Players have a lot of power and strength attached to their platform now. It’s amazing to see the likes of Marcus Rashford and Raheem Sterling using that platform for good. Rashford came from that background, where his mum was struggling to put food on the table, as is the case for a lot of families. He’s using his profile for the good of everyone. He’s a fantastic ambassador, not just for his club, but also for his family and his community. It’s the same with Sterling. They’re using their profile for the good of the game and for the good of society.

What needs to happen next? Other areas of the game need to become more inclusive – for example in coaching, management and positions on the board, plus within football clubs as a whole. We’ve got to see diversity in action and we need to get across to the black community that a football club can be a potential employer. It’s a two-way thing, because members of the black community could look at it and think they can’t get a job at a club because they don’t see anyone who looks like them.

The clubs have a lot of work to do in general when it comes to attracting a more diverse workforce. I’ve seen some of the data and diversity in some areas is still almost non-existent. The game’s done really well in developing and becoming more inclusive – and black players have no doubt played their part in that – but there’s still a long way to go.

Copyright 2024 The Arsenal Football Club Limited. Permission to use quotations from this article is granted subject to appropriate credit being given to www.arsenal.com as the source.