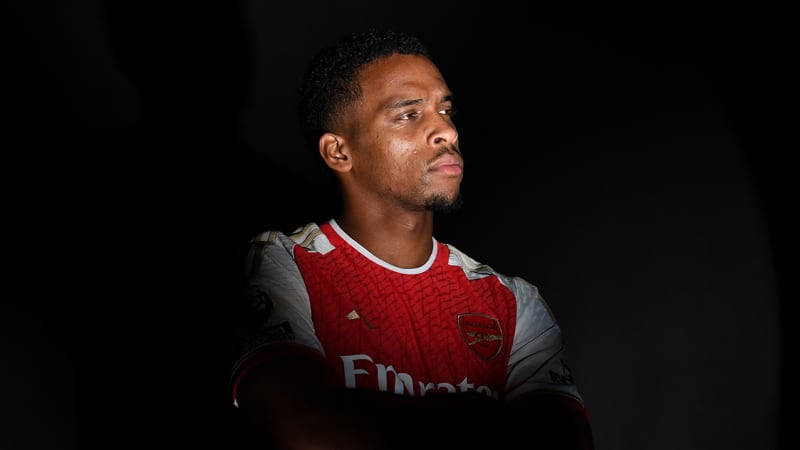

Reiss Nelson

Why representation matters

FOR BLACK HISTORY MONTH, GUEST PROGRAMME EDITOR DR CLIVE NWONKA SPOKE TO our FORWARD ABOUT his experiences of racism and how he aims to break down barriers

Black History Month exists for a reason. It gives everyone the opportunity to share, celebrate and understand the impact of black heritage and culture. In football terms, it gives us cause to reflect on the scourge of racism – a blight on the English game in the 1970s and 80s that, despite great progress and the tireless work of organisations such as Kick It Out, has never been eradicated completely – and also celebrate the contribution of so many Black players.

They stand tall in the history of Arsenal, from Brendon Batson, Raphael Meade and Chris Whyte through the greats of the George Graham and Arsène Wenger eras to the likes of Bukayo Saka, Eddie Nketiah and Reiss Nelson, not to mention a host of young academy players making their way in the game.

To mark our celebration of Black History Month today, Reiss Nelson – a young man who grew up in an ethnically diverse part of south London and has been with Arsenal since the age of nine – sat down to talk to Dr Clive, sharing his own experiences of growing up in a mixed-race household, living on a primarily Black estate and facing suspicion when he ventured beyond its boundaries.

He reflects on racism in the game, the progress that has been made – including Arsenal’s role in that progress – and, through his passion for community work, identifies an area in which we all need to work harder to keep on breaking down barriers.

Reiss, let’s start at the very beginning, with where you’re from...

I’m originally from Elephant & Castle. I’m from the Aylesbury Estate – it’s massive, one of the biggest estates in Europe – but not everyone knows it, so Elephant & Castle is easier because it’s the place that everyone knows.

It’s a diverse area, so how was it for you growing up there? Did you face issues around your race and colour, or were you purely able to focus on football?

I’d say it was a bit of both. Growing up, from the age of eight until about 12, you don’t realise the racial issues that are happening around you in certain areas. There were a lot of black people on my estate, so we felt that we were together as a group and were fine, but in and around the area, there are a lot of white people in Bermondsey, and a lot of times when you go to those areas on your own as a kid you realise certain things and have feelings that you don’t experience at home.

Then, maybe when you’re on a stairwell, you get questions: “Why are you around here?” Or in a shop, maybe a designer shop that’s a bit out of your league, you have eyes on you, and you feel a kind of presence, you know? I don’t get it now, maybe because I’m a bit more recognisable, but until I was maybe about 16 I’d have people on me all the time, asking questions. You get those little stares, and you can feel it. It’s not a nice feeling to have.

When you were young, did your parents ever speak to you about race and representation, how to manage yourself, and how to behave?

Yes and no because I’m mixed race, so my mother’s parents were Black and white and they had trouble growing up because of course being a mixed-race child back in those days wasn’t really the thing to be. So I kind of had two sides, where I would be at my nan’s house – she’s white – and she told me to be strong in what I believe in. My grandad, who’s Black, would be the same.

They came together and both had an understanding of what younger people were going through. They would say: "if you’re in that shop and eyes are on you, just let it be. You know what it’s like so don’t overreact, don’t give them an opportunity to point the finger or blame you for anything."

Who were your big role models in terms of people you looked at and thought, “That’s who I want to be”?

Being an Arsenal fan it was probably Thierry Henry, Wrighty and Jack Wilshere. They were the three people I looked up to most. With Jack, I wanted to follow his career path from the academy to the first-team, and with Wrighty it was more the amazing career he had after coming from a rough background. He comes from an estate like me, so to see him come through all the troubles and things he’s gone through – I feel like I’ve had a similar path and know some of what he went through to make it to the top.

You’re from south London, so did you gravitate towards Arsenal as a London club because they had so many Black players when you were growing up?

One hundred per cent. People like Rocky and Ian Wright, they were people that my grandad and brother would pinpoint as the players to represent Arsenal and the players to aspire to be like.

In the 1980s, with the likes of Paul Davis, Michael Thomas and David Rocastle at the club, they carried a lot of responsibility on their shoulders – pioneering Black players at a time when bananas were being thrown on the pitch. Have you ever faced that sort of abuse?

I don’t think I received a lot of abuse playing football in England. A lot of the racism I got was when I was abroad. I was in a town called Heidelberg when I was on loan at Hoffenheim, when I was 19, and it was similar to being a kid again – the look you’d get when you went into certain restaurants, or even in the supermarket there would be a lot of older people who are maybe set in their ways.

For them to see a young black boy in a predominantly white neighbourhood – without even saying anything they’d give you that look that says: “What are you doing here?” or they’d tut and walk away. Then at certain away games you’d get the monkey chants, especially when taking corners. I think at that age you kind of laugh it off, and don’t look at it as deeply, but of course it’s a deep, deep feeling.

It has to stop. I think maybe players should confront it more, until it does stop.

"Growing up, from the age of eight until about 12, you don’t realise the racial issues that are happening around you in certain areas"

I want to talk about Bournemouth last season and the last-minute winner. If you look back at the videos now you can see a hugely multi-racial fanbase. I don’t think I’ve seen that in any other stadium, possibly in the world, where you have so many Black and brown faces among the white, all appreciating football.

What’s it like for you, looking up from the pitch and seeing that multiculturism in the stands?

It’s amazing. That’s what you want to see, you know? Arsenal is a beautiful club and I think it goes back to all of the players that we had over a long period of time, and how that represents the fanbase as well. It’s a beautiful thing to see so many different faces.

Since the Premier League began in 1992, of all the players who have made their debuts for Arsenal, more than 40 per cent of them have been Black. How does that make you feel?

It’s an amazing achievement, but let’s make it more. Forty per cent is good, but why can’t we make it 80 per cent? There are so, so many talented Black players, and what it does show is that Arsenal are willing to give you a chance. I do know that certain other players have been on trial at other clubs and have felt that they didn’t get in because of their skin colour.

Really? In London as well?

One hundred per cent. And when they’ve been abroad in some cases. Is it for sure that they know that? I don’t know, but if that’s the way they feel... so 40 per cent is an amazing stat, but why can’t we make it more?

In the past, I had an experience taking a young Black player to trials at two London clubs – at one of them, he was the only Black player among about 30 kids, At the other, there were a lot more and he felt a lot safer because people and coaches looked like him.

Without naming any names, did you go to any clubs where you felt: “I can’t see myself making it here?” Or was it that with Arsenal you felt at home because there were other youth players who looked like you or came from the same background, with shared experiences?

I feel like Arsenal has been amazing for me because, like I said, there are so many people from different cultures and backgrounds. I remember coming here as a nine-year-old and there were another couple of kids from south London. Even at that age, I could see the scouting system wasn’t only focusing on one area or one group of people. It covers a wide area, which is beautiful to see. I remember Ian – he was from Colombia and lived in Kenton. I was in Elephant & Castle, which is a short train ride away, and at nine years old that was amazing. I always felt at home at Arsenal.

In terms of representation we’ve looked at players here, and the fanbase, but what do you think the wider football world should do to increase representation – including off the pitch as well, in terms of coaching or within clubs and organisations?

I guess I can only talk about things I know, in terms of football, and for me, the best thing is in terms of community action. I’m all about the community, and if there’s more happening in the community, and more players being scouted from different areas, that can only help people from all sorts of different backgrounds get recognised in whatever they’re doing. There are a lot of people from my old area who were coaches, youth workers who have gone on to do amazing things in different industries, and that has all come from being a core part of the community.

They’re helping kids always, and I think that’s something we’re lacking right now, especially in south London – there aren’t enough people active in their communities. You go to a pitch on a Monday or Tuesday and it will be empty, whereas when I was growing up the pitch was just full of kids. After school you’d see at least 10 or 15 kids, all in their school colours, all playing football, or at a youth club playing table tennis or getting mentored by Black, white, Asian people. That only helps to get you educated for the real world.

I feel like there’s not a lot of people doing that anymore. If we can have more of that, and more community workers involved in football, pushing kids towards whatever they want to do – it doesn’t have to be football, just in everyday life – that would help.

"Arsenal is a beautiful club and I think it goes back to all of the players that we had, and how that represents the fanbase"

In terms of football, just looking back on the Chelsea game, there’s something about late goals that's become a habit over the past couple of years. What is it about this team that means you can keep on hanging in there and finding these late winners and equalisers?

I think it’s the belief that we all have, no matter whether you’re starting, on the bench or even not in the squad. The belief that the boss puts in players makes us feel like anything is possible. Even if we’re 1-0 down, 2-0 down and there’s minutes to go, we still have that fire in our belly where we think: “We’re not stopping here, we’re going to carry on knocking on the door.”

We keep going, we keep pushing, and that comes from everyone: the staff, the coaches, the kit men, the players, the crowd. Everyone feels that, and when you have that sort of belief and energy only good things can happen. I think that’s why we keep getting late goals.