Be kind, no matter what. That’s one of the biggest lessons my parents taught me.

Both of them went through difficulties in their own manner - and very hard ones as well - but the way they were able to put them all behind them and be so thoughtful to everyone else is amazing. Let me explain…

My dad’s back story is interesting to say the least! He was actually born by the side of the lake – not quite a swamp, but a pond. So, because he wasn’t born in a hospital, he was actually what we’d call a bush baby, because he was delivered by his grandmother at the side of this pond. This meant that he had no birth certificate and had to prove he existed when Australia voted for citizenship in 1967 for Aboriginal people.

He grew up in Outback Western Australia as part of the Stolen Generation. For those who don’t know, that basically started when the British came to Australia. All the indigenous people were here already and the British wanted to have the children learn and work with them, and take them away from their families, and the Australian government then took on the control of Aboriginal people through the law and could do whatever they wanted with Aboriginal families.

So a lot of the kids were taken away and split up. In my dad’s case, he was raised by his grandparents, lived off the land and didn’t really have a real place in Australia, like his own culture or own home. In fact, all of his siblings were taken to Christian missions across Western Australia so he didn’t see them for about 18 months, and his school was so racist that he left after three years because there was no support for indigenous kids.

Lydia with her dad

He was so desperate to learn that he tried to get on the missions because the kids who were taken away were taught English, maths and practical skills that could result in a job. But still, nobody would accept him.

So he turned to alcohol. And that became his life for a while.

He was experiencing a lot of pain. Along with growing up not knowing who his father was, like many of the Stolen Generation, he didn’t really know where he fit in. Until one day, a missionary visited his tribe and showed him kindness in the purest sense of the word: he spoke to him and he listened to what he had to say.

From that moment, my dad went through Bible College and decided he wanted to be a travelling missionary. He gave up alcohol, packed up his guitar and then travelled barefoot and on a bicycle into communities across Western Australia, trying to help people who felt lost themselves.

We’ll pick up the rest of my dad’s story in a bit, because this is where my mum comes in…

She grew up in Oklahoma, in the United States, in a military family. It was a little bit difficult for her growing up because she didn't really feel like she belonged, so she left and went to New York City via Boston.

Lydia with her mum

After a number of years as a high school teacher, she actually became a stockbroker’s assistant on Wall Street, living and working right in the middle of New York City. It was a great career but she didn’t find it all that fulfilling, so she went out searching for a change of scenery.

One day, she was asked by her local church to volunteer to go on a missionary trip to Australia, with the aim of working with indigenous people in the middle of the desert. She didn’t think twice before packing her bags!

She moved to Australia, pitched a tent in the middle of the desert and helped as many vulnerable people as possible. In a lot of Aboriginal communities, there’s a lot of drug and alcohol abuse, as well as domestic violence, so mum would keep her tent open for women who needed somewhere safe to sleep.

Anyway, as the months passed and my mum continued her mission, word began to spread about this American woman helping people in the middle of the desert – and let’s just say it got my dad’s attention.

So after a while, they finally got introduced to one other on New Year's Eve, exchanged addresses and they wrote to each other for four months. He actually proposed to her through the letters, so when she packed up everything in both the desert and America, it was for good.

Lydia with her parents

My dad had arranged for them to get married on the site of an Aboriginal massacre. It was essentially a dry creek bed, with stray dogs and people watching. I know, I know, it sounds crazy but here’s my dad’s reasoning:

“Where something bad happens, something beautiful can come out of it.”

Kind of romantic, in a way!

So they got married and honeymooned in a cave. But when they emerged, that happiness was challenged by a lot of prejudice and racism on both sides. Dad was obviously marrying a white woman, whereas my mum was marrying a black man. There was a lot of hesitancy for a number of years but when I came into the picture and was growing up, I never felt that.

For me, it was fine around family and around people that knew both of my parents. But if it was me out in the middle of the street and walking with my dad - because I'm more fair-skinned - a comment would be thrown my way, especially at football games.

Lydia and her dad with other kids in the desert

In Australia you play all sports growing up, especially in the country towns, so I did athletics, football, tee-ball, basketball, and my dad would come to watch. I'd see him after the game and people would be like, 'Oh that's your dad?' It was a comment laced with some racial undertones and there was definitely a lot of that being thrown my way throughout my childhood.

There would be other times as well, like when I was growing up in Kalgoorlie and involved in the aborigine and indigenous side of things. I would join in with corroborees – tribal dancing – and because I wasn’t dark-skinned, it almost felt like I was being judged.

Even though I’d spent a lot of my life in the desert, learning about the land and the culture, because I didn’t look like everyone else, it felt like I didn’t quite fit in. I spoke with such an aboriginal and tribal twang, so there were words I'd say in the desert and it would be fine but when I'd say it at school, people would be like, 'Oh she's black'.

I wouldn't feel black or look black, but I'd still get judged because I didn't speak in more of an educated manner and had a different dialect. That was difficult to juggle: the colour of my skin versus what I knew and how I acted. It was all a bit of a mishmash but looking back on it, I never let it affect me.

See, there were obviously these two contrasting sides to my upbringing but I never saw it as my mum’s culture or my dad’s culture, I would just focus on what they were like as people and how they treated others, regardless of who they were, what colour they were or where they were from.

Lydia with her dad

There were times when I’d be walking down the street with my dad and we’d see someone who was an alcoholic on the side of the road. These were the days where mum would head out for work and leave us with $20 to grab some dinner. But instead of getting stuff for us, my dad would give the person our money to get a hotel for the night.

“These people need the money more than we do,” he’d say. “We’ll be OK because we’ve got a house, food and everything we need.”

He was right. Both of my parents showed me how to be kind, no matter who the person is, and they’d continue to practice what they preached throughout my childhood.

They travelled around to so many different missions and helped in so many different communities that I’m pretty sure that if I went out to the desert now, everyone would know me because of my parents’ work.

I got to see them helping people a few times and when I didn't, I had to stay at home with other families and friends. I'd go maybe a month or two without seeing my parents, and I'd have to still be at school while they were working. It taught me how to be independent but let me tell you, it wasn’t all plain sailing!

A young Lydia plays with a kangaroo

There were times I can remember having the worst temper tantrums because I was so homesick, but I just had to deal with it. It taught me that they had their job and if they could take me they would, but my mum was so adamant that I needed to be educated. I needed to make sure I graduated, that I had a future, that I was at school and didn't cut any corners. It was hard to rely on myself sometimes, but it was worth it.

Because of that, I got to be in Sydney from when I was nine, despite growing up in the desert. For me, that was huge! I couldn't believe I was in the biggest city and it was pretty crazy that I was there for two weeks, staying with people who are still my friends to this day. I find that pretty insane.

I was 11 when we moved to Canberra and it was terrible! I told my parents that I hated them, I barricaded my door with my drawers and told them I wasn't leaving. I mean it ended up being the best thing for me but at the time I was distraught!

Mum said the day that I stopped crying and being upset was about six months after we moved. It was just because I was so used to being in a tribal and country town, so when I went to Canberra - like Washington DC with the politicians, the education and no desert at all in terms of red dirt - I didn't know anybody.

My mum signed me up for football teams, basketball teams, all of them - she knew I didn't have any friends so she wanted me to get involved in things I was good at, so I could meet people.

Lydia loved to explore

Being at a ‘regular’ school probably took a bit of time to get used to as well. I remember one of my best mates said that the first time she saw me I was walking off into the big oval and looking through the grass.

“I hated you at first,” she tells me now.

“Why?”

“I don’t know, you were just so different!”

We laugh about it now but it is just because I was so different. I lived in the desert and that was something I'd do, but to her, she was watching this weird kid from the bush looking at grass. I don’t blame her for judging me because at such a young age, you just judge so quickly. That's why sport was massive for me.

Lydia was destined to play in goal

The club that I joined was probably the best place for me to be at that time. It was our local one and we'd arrived late for registration, so they told me that Division Four had whichever position I wanted to play and that I could have fun, or I could play goalkeeper in Division One. I was like, 'I played AFL and I know how to kick and catch so I'll be a goalkeeper'. In reality, I would have played anywhere – I just wanted to be in Division One.

The coach of the team was actually indigenous himself but from a different part of Australia. When he met my dad, they hit it off straight away and automatically there was a comfort level, so we'd meet the other parents and then we got to know the girls more, hang out outside of training. For me, that club really helped me get comfortable with being a goalkeeper and also be comfortable with a new city, a different vibe and new people. It really helped me to break down those barriers and meet people.

That’s the beauty of sport: it doesn’t matter who you are or how good you are, it’s all about having fun – that’s why everyone gets into it. As you get better or get older, then that fun turns into passion to become the best you can be or it continues to be fun for the social aspect.

After all, sport is all about the journey you have along the way and finding out your path. If you’re looking to pursue it at an elite level, then you need role models – and as soon as I saw Cathy Freeman at the Olympics in 2000, I knew I wanted to be just like her.

I can remember watching her with my dad so vividly. There she was, this indigenous athlete, carrying the hopes of an entire nation. Gosh, I still get tingles thinking about it. All of that pressure that she must have been under, but she was still able to go out there and win the 400m gold.

Lydia got the chance to meet her hero at the 2016 Olympic Games

I can still picture her jogging around the stadium holding both the Australian and Aboriginal flags, being so open and proud of who she is, and I think that can be a lesson for all of us. As individuals, we need to be confident in who we are and who we’re going to be. We need to surround ourselves with the right people and listen to what those people say, because they’re the only ones that matter.

They may be your parents, your friends, whoever, they love you and they’re not going to lie. What they see is who you are and that’s the most important thing. These days it’s far too easy to be distracted by what other people say, people who don’t know you very well. But if you surround yourself with the right people, you’ll find it much easier to stay true to yourself.

There’s another piece of advice I’d like to share that helped me through a tough time, and it comes from Brene Brown, a really inspiring motivational speaker, about being vulnerable and open. If you tell someone about all the fear, anxiety or insecurities that you have, it’s so much easier to work through it because it becomes a thought or something of the past. She explains it like this: through vulnerability comes strength.

The hardest thing that ever happened to me was when my dad passed away. I was 15 and didn’t speak to anyone about it for a good eight or so months. Because of that, I can’t remember an entire year of my life. But then when I turned 16, I got into a higher level of football, I got into the national team and won my first cap at 17. Through opening up, I channelled that pain into motivation and that has carried me through ever since.

I’ve been through probably the hardest thing anyone could go through at such a young age that it’s actually made me stronger, more resilient and into the person I am now. It doesn’t matter how scared, nervous, anxious or insecure you may feel, if you can show that vulnerability and talk to someone you trust, it will turn into strength and something much more powerful.

That’s why it’s so important to be kind. Because you’ve no idea who your kindness will empower next.

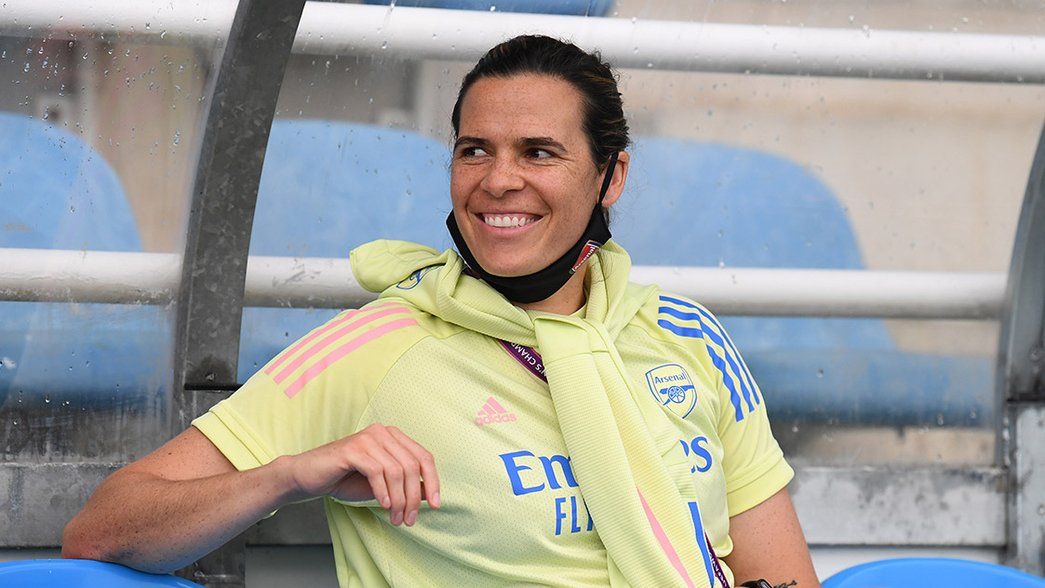

Lydia Williams

Copyright 2025 The Arsenal Football Club Limited. Permission to use quotations from this article is granted subject to appropriate credit being given to www.arsenal.com as the source.