This year we’re commemorating Black History Month by telling the story of the protagonists who have shaped or are connected with our unique history with the Black community.

Over the course of the month, we’ll profile key voices from the Arsenal family and beyond – including iconic men’s and women’s players, supporters, employees, academics and many more.

First up is Dr Clive Nwonka, Associate Professor of Film, Culture and Society at University College London and author of Black Arsenal – an upcoming book exploring the club’s place in Black British culture.

By Dr Clive Nwonka

Associate Professor of Film, Culture and Society at University College London and author of Black Arsenal

How would I define Arsenal’s connection with the Black community? There’s no precise point or phenomenon or artefact that one can use - it has to be approached and understood as a collection of factors over the course of 50 years.

When I thought of the concept of Black Arsenal, one of the principles was that it isn’t something you can easily define by a particular point or by a cultural reference.

It’s a combination of different factors that can be quite inconspicuous when viewed singularly or when not thought about in relation to each other.

It’s the way in which football culture, social culture and visual culture draw in different kinds of experiences around identities and its connections.

One could certainly find a geographical connection - Arsenal is based in Islington, which became a space of integrated, multi-racial reality in the 1960s and 1970s. A lot of the players who have gone on to become pioneers of Black Arsenal were locally recruited.

North London has always been a region of multi-culture that seemed to allow for players and the fan base to gravitate towards Highbury. That expanded to almost become shorthand for supporting Arsenal if you were a football fan from London. It’s hard to describe in easy terms but in the 1970s, Arsenal was seen as a space where Black supporters could enjoy football and see themselves on the pitch, which was removed from the violent iterations of racism that we were witnessing and experiencing in other stadiums in the UK, and particularly in London.

My research leads me to believe that that caused some beginnings of identification on the pitch and on the terraces that built out over time and expanded to something much more identifiable.

London’s such an interesting place because there’s multiculturalism everywhere - however integration is a completely different concept. We often tend to conflate the multi-cultural experience with an integrated one.

Terraces are a sight of multiculturalism and integration as well. When you go to the stadium and examine what happens in the stands and on the streets - for example Holloway Road - there is something very distinctive and specific about the integrated multi-culture around Arsenal that is unique.

There is a connection between geography, between local environments and what we see within fan and terrace culture - but it’s an undefined exploration. My own hypothesis is that pioneers help.

Arsenal have had pioneers - players who became visible role models in spite of suffering from racism, to allow the club to be perceived by Black people as a much safer haven than other sporting arenas.

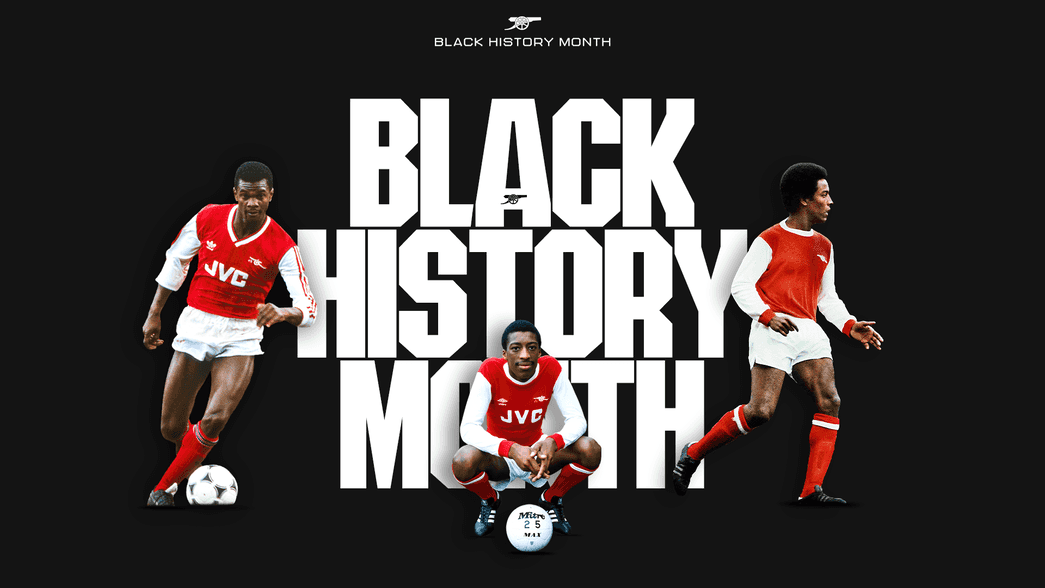

It goes back to Brendon Batson - Arsenal’s first Black player - and the work he did, along with people like Paul Davis, Chris Whyte, Gus Caesar and Raphael Meade. Often those players have been lost in the history of Black Arsenal. Everything we enjoy now about Black Arsenal - in terms of the visual culture, the use of urban sub-cultural practises like grime music, and players who star on the pitch - is only possible because of the more vicious experiences in the 1970s and 1980s when there was a danger associated with being on the pitch that was undertaken by those players. That needs to be acknowledged, championed and celebrated by the club.

Brendon Batson in action for Arsenal against Wolves in 1973

Your nascent experiences can often condition the way you see the game, or the way the game sees you. There is a difference in some circumstances between the football culture we saw in the 2000s and the pioneers who went through times where racism was permissible and actively demonstrated on the terraces across the UK. That’s not to say that those who came through later wouldn’t have had negative experiences, because they did.

Spectators in the 1980s would absolutely have heard overt racist chanting, they would have seen bananas being thrown towards the very few Black players who had endured enough to make it into the first team and become visible. How many players were lost to the game? How many didn’t make it to the top division, where they could have become influential to a new fanbase? Black people came into football by seeing other Black people on the pitch - and often that demanded television.

There’s something really important in how visibility impacted that experience. But to get to the stage of visibility, there would have been horrendous endurances of racism at other grounds. At the same time as trying to make it at a very prestigious football club, these people were suffering horrendous racism.

As for the here and now, I think there is still so much more that needs to be done - because of what the club represents.

Look at the Found a Place Where we Belong stadium mural - the multi-cultural aspect of that piece could not be super-imposed on any other stadium in the country, because it wouldn’t be reflective of that fanbase. But at Arsenal it is - that’s very unique, very magical and very powerful about this organic experience of Black Arsenal, that does need to be left to exist on its own.

A section of the Found A Place Where We Belong artwork

Yes, let’s recognise Black contributions and Black pioneers - but there will always be a Black fanbase at Arsenal and there will always be lots of multiculturalism in the stands.

There is a need for remembrance - and it pleases me that this campaign relating to Black History Month is taking place. Football has changed dramatically in the last 10 years but sometimes we need to think about how the fanbase, players and staff are still having to deal with racism on a daily basis. There has to be space in the present day for the cohabitation of celebrating what we have while recognising and intervening in what those experiences are.

But we should still celebrate what we have today. Arsenal have something that is immensely precious, which needs to be protected and preserved at all costs. That makes Arsenal much more than a football club - it makes it part of cultural and social life, that is important to Black people and that Black people find a safe place, a home. That needs to be explored and cherished, and not exhausted.

How Arsenal in the Community are marking Black History Month

By Samir Singh

Arsenal in the Community

Arsenal in the Community have been celebrating Black History Month for a long time now. We generally go into local primary schools and ensure we’re celebrating achievements in the Black community. This year we’ll be delivering 26 different History Month-focused workshops in schools across the borough, as well as to community groups and grassroots football groups. The workshops have a different theme each year - this year it’s to celebrate Black women, both on the pitch and off it too. Celia Facey, who is one of our local football coaches, is a fine example of that. This year, we’re encouraging children to draw pictures of their Black female role models. The kids love it - they’re really engaged in the sessions and are quick to make the connection between Arsenal and Black History Month.

There’s naturally always a focus on history when it comes to Black History Month, which makes total sense - and we’ve previously interviewed the likes of Brendon Batson, Paul Davis and Chris Whyte.

But we’re also keen to recognise what’s going on right now. The message from our community is consistency: we don’t want to only celebrate the Black community in October, it’s something we do all-year round.

In bygone years, we funded a statue at Whittington Hospital, commemorating the nurses of the Windrush generation. We’re involved with Islington Council’s 365 efforts to ensure Black History Month isn’t something that’s just relevant for one month, but throughout the whole year.

There are so many positive role models for children. For example, when you look at Black individuals recognised in the Football Black List over the years, you’ve got the likes of Celia and Beverley Nicholas as well as players like Rachel Yankey, who Arsenal in the Community worked with when she was a kid.

Copyright 2025 The Arsenal Football Club Limited. Permission to use quotations from this article is granted subject to appropriate credit being given to www.arsenal.com as the source.